Dynamik der Kreise, Resonanz der Räume

Die schöpferischen Impulse der Wiener Moderne

Edward Timms

edition seidengasse: Enzyklopädie des Wiener WissensISBN: 978-3-99028-233-5

21,5×15 cm, 288 Seiten, m. Abb., graph. Darst., Kt., Hardcover

24,00 €

Lieferbar

In den Warenkorb

Leseprobe (PDF)

Kurzbeschreibung

Das Ungewöhnliche an diesem reich illustrierten Buch liegt in dem Versuch, die schöpferischen Impulse der Wiener Moderne innerhalb der zeitgeschichtlichen Spannungen kontinuierlich von 1890 bis 1940 zu verfolgen. Dadurch wird eine genaue Ortsbestimmung der daran beteiligten Kreise entwickelt. Hervorgehoben werden die Dynamik der Kreise und ihre Verflechtung mit der erotischen Subkultur; die Auflockerung der Geschlechterrollen im Zuge der Frauenbewegung; eine mit der Sonderstellung der Wiener Juden verbundene Macht der Marginalität; das Kaffeehaus als Drehbühne im Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit; und die politisch instrumentalisierte Krise der musikalischen Kultur. Eine multimediale Kunstszene machte es möglich, im Rahmen einer neuen architektonischen Raumkunst eine gewagte Körpersprache zu entwickeln.

Nach dem Zusammenbruch der Monarchie und dem Durchbruch der Sozialdemokraten zur Herrschaft im Roten Wien wird der Kampf um die ideologische Hegemonie in der Ersten Republik virulent. Um die Minderwertigkeitskomplexe des zusammengeschrumpften Staates auszugleichen, wurden kulturpolitische Initiativen gestartet, von Eheberatungsstellen und Kinderkrippen über Theater- und Musikfeste bis zu philosophischen Seminaren und Kongressen der Pan Europa- und Zionisten-Bewegungen. Gleichzeitig trugen der Aufstieg der Hakenkreuzler und die neuen Medien wie Kino und Rundfunk zu einer Zuspitzung der politischen Konflikte bei. Erst nach dem Anschluss und der erzwungenen Emigration von vielen Kunstschaffenden gewannen die von Wien ausgehenden Innovationen ihre weltweite Resonanz als Birth of the Modern.

Nicht nur die großen Geister der Moderne werden in diesem Band gewürdigt, sondern vor allem der Strukturwandel der Wiener Öffentlichkeit in den letzten Jahren vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Um jede der führenden Gestalten – Herzl, Freud und Mahler, Altenberg, Kraus und Kokoschka, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann und Adolf Loos, Berta Zuckerkandl, Rosa Mayreder und Genia Schwarzwald – bildete sich ein dynamischer Zirkel von Adepten, und durch die Verflechtung dieser Kreise miteinander entstand auf kultureller Ebene ein elektromagnetisches Netzwerk, das erstaunliche Energien auslöste. Mitbedingt wurde diese Kulturblüte durch die Initiativen von emanzipierten Frauen und die Unterstützung von kunstsinnigen Mäzenen, nicht zuletzt aus dem aufstrebenden jüdischen Bildungsbürgertum. Die Moderne wird aber als ein komplexes Phänomen verstanden, dem mit Schwarzweißmalerei nicht beizukommen ist. Denn im Wien Karl Luegers gab es schöpferische Wechselwirkungen zwischen progressiven und beharrenden Tendenzen, jüdischen Intellektuellen und bodenständigen Politikern, Avantgarde und Gemeinde.

Von den Kaffeehäusern Wiens gingen geistige und künstlerische Impulse aus, deren Auswirkungen in den Kulturkämpfen der Ersten Republik das Thema der abschließenden Kapitel des Buches bilden. Hier geht es um die politisch gespannte Gruppendynamik, die von der Sozialdemokratischen Kunststelle, der Christlichsozialen Kulturpolitik, der Deutschnationalen Anschlussbewegung und ähnlichen Strömungen geschaffen wurde. Sogar die Philosophen des Wiener Kreises und Wissenschaftler der Universität wurden in den Tumult des Hegemonialkampfes hineingezogen. Es lag vor allem an der internationalen Wirtschaftskrise um 1930 und der dadurch erzeugten Erschütterung demokratischer Institutionen, dass der Kampf um Wien mit der Niederlage der Moderne und der erzwungenen Emigration ihrer Hauptvertreter endete. Rassesieg in Wien hieß dann die monumentale Buchpublikation eines völkischen Studentenführers. Doch für Edward Timms, der als englischer Kulturhistoriker die Ereignisse aus einer distanzierten Sicht betrachtet, hatte auch jene Tragödie schöpferische Auswirkungen, indem die Initiativen der Wiener Moderne durch Vermittlung der Exilanten eine weltweite Verbreitung fanden.

[Enzyklopädisches Stichwort]

[edition seidengasse · Enzyklopädie des Wiener Wissens, Band XVII |

Hrsg. von Hubert Christian Ehalt für die Wiener Vorlesungen, Dialogforum der Stadt Wien]

Rezensionen

Arnhilt Johanna Hoefle: [Review]This copiously illustrated panorama of Viennese culture before and after the First World War follows in the wake of challenges to Carl Schorske’s account of ‘Vienna 1900’ and its supposed retreat into the aesthetic realm after the political failure of liberalism (see his Fin-de-Siècle Vienna, New York 1981). As a synthesis of substantial multi-disciplinary research – not least of Edward Timms’s own decades-long work on Karl Kraus, Adolf Loos, Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis, Theodor Herzl and Zionism, and the central role of David Bach and the Social Democratic Kunststelle in ‘Red Vienna’ in the 1920s – the book aligns itself with one specific alternative to Schorske, focusing on Vienna’s ‘critical modernism’ – a project in the spirit of Albert Fuchs’ Geistige Strömungen in Österreich. 1867–1918 (Intellectual currents in Austria. 1867–1918, Vienna 1949), which had, however, excluded the arts.

Timms is less inclined than some to question Vienna’s ‘exceptionalism’ when he lists thirty-one factors that drove change: some are common to other countries (a progressive, prospering educated middle class; cross-fertilization between art forms), others Austria-specific (ironic modernization of the ‘Habsburg myth’) or unspecific (‘reforms after the turmoil of World War’). While graphically presenting the ‘dynamics’ and ‘creative synergies’ of the pre-1914 ‘Viennese circles’ and then their polarization in the interwar period, he adapts Jürgen Habermas’ model of ‘structural change’, prioritizing the coffee house among the institutions that used the ‘gentle persuasion’ of radical ideas to defy the hegemonic powers blocking social reform. The driving factors are: intellectual, erotic, patronage and the national economy – strata that are perhaps comparable to Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘fields of cultural production’.

Rather than theorizing further, Timms demonstrates interconnections between the arts in an impressive range of case studies, for example, the ‘synergies between extravagant phantasy and pure function’ in Klimt’s Beethoven frieze within the space of Hoffmann’s Secession building. The loosely historical model is thus complemented by topographies of ‘spatial syntax’ that work both metaphorically (the city as a readable code) and physically (the proximity of circles). However, the photographic record of writers’ studies is used to challenge the myth of the coffee house as the ‘scene of writing’ – notwithstanding Peter Altenberg and Josef Hoffmann. Klimt’s ‘male gaze’ is chastised, but the creativity of ‘erotic’ discourses is differentiated from Stefan Zweig’s account of sexuality and the subculture of chambres séparées: even jealousies in ménages à trois are claimed for a ‘system’ of creative reciprocity (as are Alma’s ‘devil’s pact’ with Mahler, and Kokoschka’s series of fans for her).

For the role of women in salon culture, Timms draws upon the unpublished diaries of art historian Erica Tietze-Conrat, an exemplary female professional, like the photographer Dora Kallmus. The Austrian women’s movement, less militant than the suffragettes, is credited with advocating progress through education and defiantly pioneering marriage counselling agencies – later consolidated by the municipal health department under the Socialist Julius Tandler. Rosa Mayreder’s historically important critique of sexual power relations and gender is acclaimed. Her association with the Soziologische Gesellschaft is cursorily noted, and Timms draws on documentations of progressive societies and initiatives such as the Akademischer Verband für Literatur und Musik in Wien and the Schwarzwald School – but not other reforming or innovative hubs like Robert Scheu’s Kulturpolitische Gesellschaft, or the Handelsmuseum, given the latter’s proximity in the Berggasse to that other ‘space for solutions’, the Vienna Psychoanalytical Association, which is well covered, along with further mutations of psychoanalytic method: Alfred Adler’s ‘Ambulatorium’, Sabine Spielrein’s challenge to the phallocentric definition of sexuality, and Wilhelm Reich’s sexual radicalism.

Yet for Timms, creativity sprang from the co-existence of extremes, not from sublimated sexual repression or sheer libertinism. He frames the well-known Jewish contributions to innovation in a sociological model of exclusion and mobility (Robert Park’s ‘dynamic marginalities’).

In a brilliant section on Herzl that complements Schorske (Herzl and Freud as ‘conquistadors’), opposition to the Zionist leader is traced locally, both to the ‘palace’ of the Neue Freie Presse and to the synagogue, whereas his international ambition is reflected in a group photo on the Palestine-bound ship in the quest for a ‘Jewish state’ – but also negatively, in his journalistic willingness to serve the Grand Vezier’s propaganda at the expense of the Armenians, in order to gain concessions in Palestine. Herzl’s tolerant, multicultural Zionist utopia is ironically contrasted with later Palestinian-Israeli reality. For Vienna, despite the workers’ movement’s marches since 1 May 1890, Timms suggests that ‘the street’ and the outer suburbs challenged the cultural venues of the city only after 1918 – often in violent clashes or ideological shows of force. Workingclass education, dating from pre-war in Ottakring, expanded post-war when David Bach’s Volkshaus der Kunst presented an alternative to the successful ‘non-political’ Konzerthaus, while the medium of cinema was proclaimed by Alfred Polgar to have replaced the monarchy as a unifying force.

Timms finds little insight or lasting value in the resurgence of a Catholic culture and its organizations and passes a damning judgement on its völkisch and authoritarian elements and the perversion of Christian ideals as preparing the ground for fascism, which he epitomizes in a set of contrasts between the duelling fraternities and those ‘creative circles’ to which so much of his research is devoted. The ‘Vienna Circle’ of Moritz Schlick and Otto Neurath is, for him, a microcosm of the ‘unfinished project’ of Viennese modernism. Anti-modernism and antisemitism had pervaded student life long before the Nazi assault on the Anatomical Institute in 1933 and Schlick’s murder in 1936. The innovators and their fate in exile are exemplified by Neurath’s and Anna Freud’s separate legacies to Britain. While these telling postscripts serve in lieu of a conclusion, it is a pity there is no bibliography in this volume of the Enzyklopädie des Wiener Wissens, given Timms’ ability, through intertwined micro-analyses and broad synthesis, to evoke the richness and impact of that culture – also for the Austrian (or German) reader of today.

(Arnhilt Johanna Hoefle, review in: Austrian Studies #24, February 2017)

Weitere Bücher des Autor*s im Verlag:

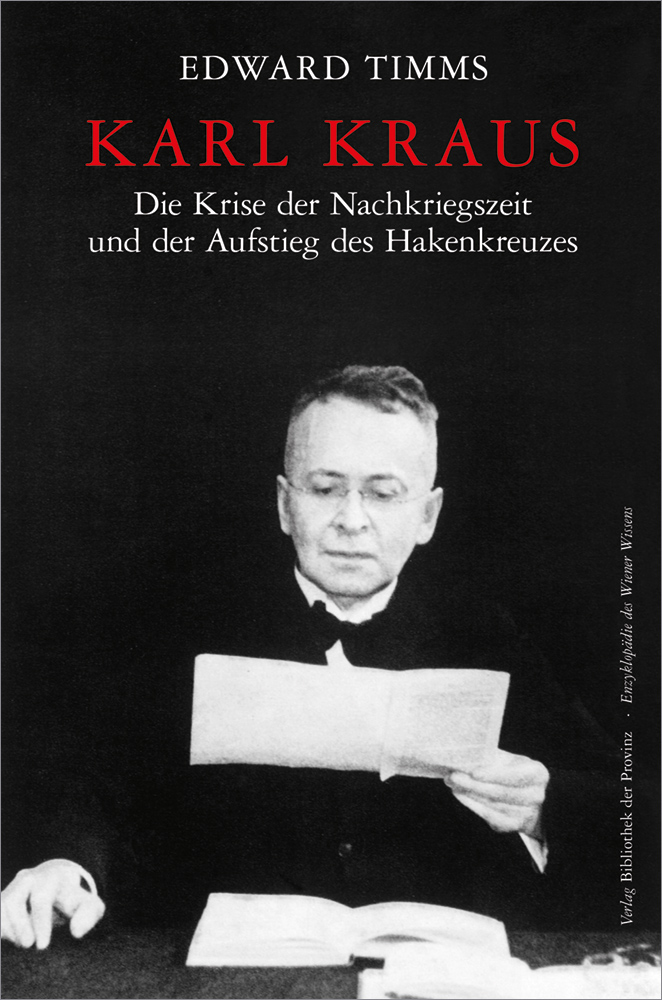

Karl Kraus – Die Krise der Nachkriegszeit und der Aufstieg des Hakenkreuzes